Post-Brexit trade negotiations will be less fearsome than imagined

Civitas, 13 June 2016

By Michael Burrage

Roberto Azevêdo, the WTO’s director-general entered the debate about Brexit in an interview with the Financial Times. It attracted wide media attention partly because he issued a stark warning that ‘pretty much all of the UK’s trade [with the world] would somehow have to be negotiated.’ And also because his bluster seemed so extraordinarily muddled. Although the UK was a founder member of the WTO, he decided ex cathedra it was no longer a member because it has allowed the European Commission to negotiate on its behalf since 1973. And although a non-member, post-Brexit UK would, according to him, somehow or other be prohibited from lowering tariffs if it wished, and be forced against its will to impose and collect tariffs on goods from other countries.

It would be entertaining to see how that wholly unprecedented scenario played out. But he ended on a point that everyone would agree. ‘It is a very important decision for the British people. It is a sovereign decision and they will decide what they want to decide. But it is very important, particularly with regard to trade … that people have the facts and that they don’t underestimate the challenges.’ Or of course, exaggerate them.

The Regional Trade Agreement Information System (RTAIS) of his own organization shows that the 36 trade agreements with 58 countries negotiated by the European Commission and currently in force are overwhelmingly with small and mini-countries, which in 2014 accounted for just 6 per cent of total UK goods exports, with a further 8.1 per cent going to the EFTA countries. Since only a minority of these agreements refer to services, their coverage of UK services exports is still smaller, just 1.85 per cent of total UK services exports, with a further 7.2 per cent going to the EFTA countries. For its ‘heft’, ‘clout’ and ‘negotiating muscle’, the EC has negotiated very few agreements of benefit to UK exporters over 40 plus years of negotiation. It may be a heavyweight, but it has long preferred to negotiate with flyweights.

This means that the UK would have to renegotiate with countries receiving 14.1 per cent of its goods exports, (plus the 44% going to the EU), and just over 9 per cent of its services exports (plus the 37 per cent going to the EU). This is rather less than the ‘pretty much all’ mentioned by Snr Azevêdo, though it would no doubt be a significant task. Would it be as ‘tortuous’ as he suggested?

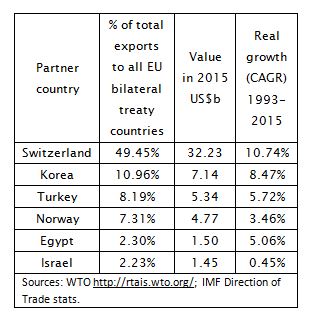

Thirty-six trade agreements with 58 countries sounds an onerous administrative and negotiating task, but the RTAIS, along with data from IMF, shows that 80 per cent of UK goods exports covered by these agreements are with just six countries as shown in the box below. Five of these six also happen to be among the fastest-growing UK export markets. Indeed, if the UK’s post-Brexit negotiators focussed on the first two they would be halfway home. Both happen to be energetic pro-active trade agreements negotiators.

The plain sad fact is that the limited evidence as we have indicates that most of the other agreements negotiated by EU have not benefited UK exports at all. So even if the post-Brexit UK failed for a while to negotiate agreements with many of the rest of them, their failure could hardly be significant. Moreover, most of the partner countries have low tariffs on non-agricultural goods, which are less than normal fluctuations in the exchange rate of sterling.

The plain sad fact is that the limited evidence as we have indicates that most of the other agreements negotiated by EU have not benefited UK exports at all. So even if the post-Brexit UK failed for a while to negotiate agreements with many of the rest of them, their failure could hardly be significant. Moreover, most of the partner countries have low tariffs on non-agricultural goods, which are less than normal fluctuations in the exchange rate of sterling.

In services, the renegotiations would be similarly delimited and focused. Switzerland, Norway and Korea together account for 8 per cent of all UK services covered by these EU agreements, leaving just one per cent for all the other EU agreements with the rest of the world put together.

In sum, post-Brexit UK has to prioritize renegotiations with three countries Switzerland, Korea and Norway if it wanted to replace the core of the lapsed EU agreements. In reality, of course, it would seize the opportunity to take advantage, at long last. of the immense comparative advantages it enjoys in services trade (by virtue of its language, and the exceptional global reach of its professional and educational institutions) , improve the old agreements and negotiate many new ones.

This leaves the very biggest renegotiation of all, with the EU itself, about which there has immense speculation and some apprehension based on the misunderstanding that EU membership and the Single Market have been of great benefit to UK exports.

They haven’t. More than 100 non-members countries routinely export goods to the EU under WTO rules, the ‘worse possible option’ according to Mr Osborne. Forty of them exported goods to the value of $1billion or more in 2015. The exports of 36 of these larger exporters to the EU, over the years 1993 to 2015, grew more rapidly than those of the UK.

Data on the exports of services to the EU is more limited but it shows that the exports of sixteen non-member countries have grown more rapidly than those of the UK over the years 2004-2012.

In short, non-members countries not only have access to the Single Market, but exporting to it under WTO rules, they have been more effective that the UK. If the post-Brexit negotiations are strained, testy and prolonged, the UK need not bend over to make immense concessions, as Mr Cameron continually anticipates it must. In fact, it need not be alarmed at all. 36 countries have shown the worst possible option is not so bad after all.

Michael Burrage is the author of Myth and Paradox of the Single Market and The Eurosceptic’s Handbook