The current position of overseas trade and net wealth and where we are heading

Roger Bootle and John Mills, September 2016

Recently the UK has been running a very large current account deficit – around £90bn per annum, or 5% of our GDP – matched by borrowing and sales of capital assets to finance the shortfall of overseas revenue over expenditure. How has such a large deficit come about? Is this sustainable? How can such a large deficit be good for the economy? What consequences does it have? If we want to reduce the deficit, or even turn it into a surplus, what policies are there available to the UK authorities to enable them to achieve this? These are the questions that we try to answer in The Real Sterling Crisis. But before that we must first tackle a niggling issue of measurement.

Recently the UK has been running a very large current account deficit – around £90bn per annum, or 5% of our GDP – matched by borrowing and sales of capital assets to finance the shortfall of overseas revenue over expenditure. How has such a large deficit come about? Is this sustainable? How can such a large deficit be good for the economy? What consequences does it have? If we want to reduce the deficit, or even turn it into a surplus, what policies are there available to the UK authorities to enable them to achieve this? These are the questions that we try to answer in The Real Sterling Crisis. But before that we must first tackle a niggling issue of measurement.

Are the balance of payments figures reliable?

The short answer is ‘no’. All macro-economic data are unreliable but the data on overseas payments may be particularly so. And this is especially true when economies pass through rapid structural change, as the UK has done over the last 30 years.

Indeed, we know that if you aggregate all the current account positions in the world you find that the world as a whole is in deficit. Yet until we start to trade with Mars (or some other planet) this cannot be. Clearly there is a significant measurement problem.

The balance of payments figures must balance – that is to say, if there is an excess of imports over exports the money to pay for this needs to be found from somewhere. We can sell assets or borrow money. In an ideal world there would be reliable statistics available on all parts of the balance of payments. Unfortunately, we do not live in such a world. The truth has to be pieced together from incomplete data.

Suppose that there are exports or sources of overseas income that the statisticians don’t record. For any given reported imbalance of trade in goods, if recorded income from services (or property income) does not match this deficit then it must be presumed that some sort of capital inflow has provided the finance (or the government’s foreign exchange reserves have been run down).

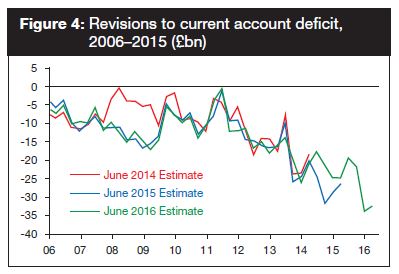

The UK is particularly prone to such under-recording since its service sector is so big and it is heavily involved in international capital markets. This means that the UK’s current account deficit is probably overstated by the official data, and the balance of payments data are prone to frequent, and sometimes substantial, revision. Figure 4 shows the current estimate for the current account deficit relative to estimates made over the previous two years. In some periods, the revisions have been quite substantial, although it doesn’t alter the overall picture.

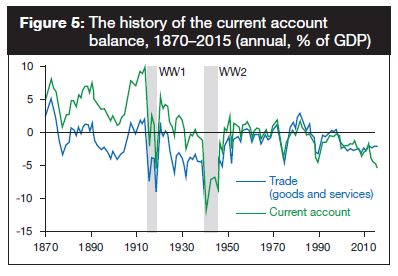

Indeed, it is unlikely that mismeasurement can occur on a scale sufficient to eradicate the deficit, or even substantially to reduce it. The recent trend in the deficit has been profoundly adverse, as shown in Figure 5. To explain this deterioration, the various distortions that we know about would have to have been getting worse. And it is not as though the deterioration in the UK’s current account position is without explanation. We know full well why it has deteriorated. We do not need an alternative explanation founded on mismeasurement. The poor performance of Britain’s overseas trade is part of a wider pattern of disappointing performance.

An overall economic perspective

That said, the performance of the UK economy since the 2008 financial crash has not been bad compared with many other western countries, although it has been much worse than some parts of the world, particularly around the Pacific Rim. We have much to be thankful for and, when criticising our record, some reasonable perspective is therefore required.

There may be deficiencies in the way our economy is structured and it may in a number of important respects be out of balance, but its absolute performance still compares reasonably well with much of the rest of the world. Ranked in order of size, measured at market exchange rates, the UK economy comes in at number six, behind only the USA, China, Japan, Germany and France.

In terms of gross domestic product (GDP) per head on a purchasing power parity basis, however, our performance has clearly slipped. As measured by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) we come in at 29 out of 188 countries, 29 out of 188 according to the World Bank and 40 out of 230 measured by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). The UK therefore has a very substantial economy with average living standards which are higher than in many other parts of the world, but we have lost our historic pre-eminence and many other countries have already overtaken us, while others are threatening to do so as our growth rate lags behind theirs.

The UK’s relative prosperity is partly the result of the fact that the Industrial Revolution started here and we have therefore been increasing our output per head over a long period of time – much longer than in many other parts of the world. During the 19th century, the UK had a higher level of GDP per head than almost anywhere else, although the USA was catching up fast. Clearly we have slipped back some considerable distance from this enviable position since then.

The crucial issue for the future is whether this tendency for us to lose ground in relation to other countries is going to continue and whether our relatively low rate of growth, which is responsible, is likely to be maintained.

Predicting future economic outcomes is always fraught with problems, because there are so many variables. But there are several key reasons for worrying that, even after post-Brexit anxiety has run its course, and even without anything unexpected going wrong, the UK economy may grow slowly over the coming few years.

Weak investment

The first major UK economic weakness is that the proportion of our GDP which we invest rather than consume every year is desperately low. In 2015, excluding Research and Development, it was 13%. Some context for realising just how low this percentage is given by the fact that the world average, measured on a comparable basis, was 25.3% and for China it was 47.8%.

Admittedly, China’s investment share in GDP is abnormally high. Not only is much of this investment wasted but the excessive rate of investment threatens to cause a sharp drop in GDP growth – or even a recession – if it adjusts sharply. The Chinese authorities face the difficult task of reducing the share of investment in GDP and increasing the share of consumption.

But, putting China aside, the UK’s investment share is low compared to most industrialised countries. As with many other issues in economics, there are considerable measurement difficulties associated with investment spending. Considerable amounts of spending on intangibles, including software development and branding, may achieve significant commercial advantage for individual firms – and real income gains for the economy as a whole – yet may be misclassified in the national accounts.

Because of the structure of the UK economy it is possible that the UK has a disproportionately large share of such spending. Accordingly, appropriately measured, the UK’s investment rate is probably not as low as the official figures imply. Nevertheless, it is highly unlikely that measurement issues can explain more than a small fraction of the UK’s recorded investment deficiency.

There is worse news, however, in the detail. Of the UK investment total in 2014, only 21% was spent on the type of investment – manufacturing broadly defined – which is most likely to increase productivity. Of the remainder, 17% was spent by the public sector on roads, schools, housing, etc., all of which may be highly desirable on social grounds but which do little directly to increase output per head and hence the growth rate in the short-term. Of the other remaining 62%, just over half was spent on private sector housing construction and the remainder on building commercial premises and service sector activities such as opening new restaurants, none of which, again, contribute significantly to productivity increases.

Thirteen per cent is a very low investment percentage, but when depreciation – running in 2013 at 11.4% of GDP – is deducted from it, only about 3% is left. Faced with these figures, it is not difficult to see why productivity in the UK is virtually static. Furthermore, 3% of GDP – just over £50bn – is not even sufficient to keep up the value of our accumulated capital assets in relation to our rising population, which is currently increasing by at least 500,000 people a year – about 200,000 from indigenous growth and 300,000 from immigration.

If you divide the total accumulated capital assets of the UK – worth £8.5trn at the end of 2014 according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) – by the total population of the UK, which was then 64.6m – you reach a figure of about £130,000. To avoid diluting down our accumulated capital, we therefore need to spend at least 500,000 x £130,000 – i.e. £65bn – every year just to avoid slipping backwards. Clearly, we are a very long way from doing this. With no net investment per head of the population taking place at all, unless we benefit substantially from some other favourable extraneous factor, it is not realistic to think that we are going to see output per head going up to any significant extent.

Manufacturing squeezed

The second major problem with the UK economy is that we have allowed our manufacturing sector to decline to an extremely low level. As late as 1970, almost a third of our GDP came from manufacturing. The share is now barely 10%.

The absence of good quality manufacturing jobs has contributed strongly to the increases in both regional and socio-economic inequality which have been such a pronounced development in recent decades. Moreover, if manufacturing is the strongest source of productivity increases, the smaller the proportion of GDP that it comprises then, other things equal, the lower the rate of productivity increase in the economy as a whole.

Manufacturing plays a key role in our foreign trade. Despite our small manufacturing sector, about 55% of all our export earnings are from goods rather than services, and although we have a substantial foreign trade surplus on services, this is more than offset by a much bigger deficit on goods – £88bn compared to £126bn in 2015. As a result, we have not had a trade surplus since 1982 or an overall current account surplus since 1985.

The UK’s problem – reflected across much of the western world – is that internationally tradable low- and medium-tech manufacturing has been largely wiped out by competition from Asia, leaving us dependent on high-tech exports – aerospace, aircraft engines, pharmaceuticals, motor vehicles and arms sales. Over and above this, in many key markets, the UK has lost out to other developed countries.

There is a view that we need not worry about manufacturing’s dedicate. We should simply accept it and rely on services, where we have a strong comparative advantage. We disagree with this view.

The problem is that the sectors in which we excel, important though they are, do not produce enough to fill the gap between our overseas income and our overseas expenditure. Moreover, they, in turn, are also eventually going to be vulnerable to competition from lower cost countries.

As well as being subject to other pitfalls. Can we – and should we – be confident, for instance, that the City of London will retain its pre-eminent position? And what we do if its earnings fell back significantly?

We don’t think we can or should lay down what proportion of the economy should be accounted for by manufacturing. That is for the market to decide – once the exchange rate is roughly at the right level. But, given the importance of manufacturing in international trade, and given the plunge in the UK’s share of manufacturing in GDP, and the price sensitivity of manufacturing output, we would be surprised if a substantial improvement in the UK’s trade balance could be achieved without it being accompanied by a significant rise in manufacturing’s share in GDP.

The current account

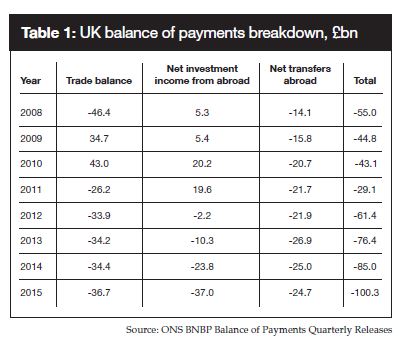

Our weak trade balance is a major contributor to the poor state of our overall current account position. The table below sets the scene.

While our trade deficit, although substantial, is reasonably stable, our net income from abroad has recently seen a very sharp deterioration. From being nearly £20bn in surplus as recently as 2011, was a negative £37bn in 2015 – a massive negative swing of £57bn.

There is inevitably some volatility in these figures, and there may well be some improvement in them over the coming years. But a significant part of this deterioration is itself a product of the UK running large current account deficits over many years. Such deficits worsen the UK’s net asset position and, other things equal, this will lead to a weaker investment income balance. This, in turn, leads to an even weaker net asset position. There is, therefore, an underlying highly adverse trend to our net income from abroad which is likely to produce major problems for us in future. (A higher exchange rate also has the effect of worsening the investment income balance as it diminishes the sterling value of income earned abroad, while leaving the sterling value of income earned by foreigners in the UK unchanged.)

The speed of this deterioration has probably been increased by the way that our deficits have been financed. Whereas in the past it was normal for the UK to attract fixed interest capital (which was held in bank deposits and/or bonds), while the UK typically invested abroad in real assets and/or equities, which tended to have a higher rate of return, in recent decades the UK has taken in a higher proportion of direct investment and equity capital, thereby worsening the relationship between the income earned on foreign assets and the income paid out on foreign assets held in the UK.

Net transfers abroad are also on a rising trend. The largest component is our net contribution to the European Union, which ran at £11bn in 2015. After Brexit this should fall back sharply – hopefully to zero. The remainder is split roughly evenly between net remittances abroad, which are likely to go up if migration to the UK continues at its current very high level, and foreign aid programmes, to which all our major parties are committed. The net result of all these trends is that the UK’s overall balance of payments deficit exhibits a strongly rising trend. In the first quarter of 2016 it reached 6.9% of GDP. For 2015 as a whole, the deficit was 5.4% of GDP. In percentage terms this was easily the highest deficit in the whole of the developed world.

Trade not the problem?

Given that the main culprit for the recent deterioration in the overall current account balance is the deterioration in net investment income, while the trade deficit has been broadly stable, there is an argument that exchange rate policy, which is designed to affect the trade balance, is otiose. It is to the change in investment income that we need to direct attention.

But this argument is misguided on five counts:

- The surprising thing is not that the investment income balance has deteriorated recently but rather that it held up so well for so long. This may well be explained by the risky nature of many of the UK’s international assets. In any case, although we can hope that it will improve, we cannot take this for granted. We need to take the current level of the investment balance as it is.

- As it happens, a lower exchange value for sterling would improve the net balance of investment income.

- While the size of the trade deficit at about 2% of GDP is much smaller than the overall current account (about 5%), nevertheless, it is still a deficit. Why is it deemed OK for the UK to be running a trade deficit of ‘only’ 2%, when Germany runs a huge surplus?

- If the UK is to run at a high level of domestic demand and to use up all available spare capacity, the trade deficit would be higher.

- Much of the wider adverse economic impact of the current account deficit, including the effects on UK manufacturing, the regional divide and inequality, stem from the trade deficit.

From creditor to debtor nation

The effect of these large and chronic deficits has been to turn the UK from a net creditor to a significant net debtor. ONS figures do not show a consistent pattern year to year but between decades there has been a very marked change. Whereas in the 1980s the UK always had assets exceeding liabilities, during the 2000s liabilities exceeded assets by about £82bn throughout the decade. By 2015 this figure had risen to almost £270bn.

These figures highlight another major concern about the UK economy which is the volume of debt which it now sustains, not least that part of it owed by the government. Clearly, the government deficit needs to be reduced to much more manageable proportions. The key issue is whether this can be done if the country continues to have a foreign payments deficit as large as the one currently being experienced.

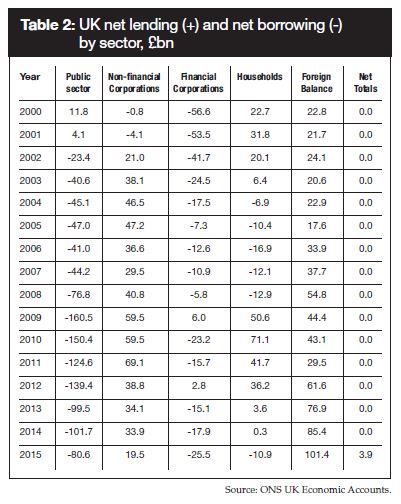

It is a fallacy of composition to believe that what might be the obviously sensible way for an individual whose expenditure was greater than his or her income to bring the two back into balance – by cutting expenditure or increasing income – would work in the same way for the economy as a whole. What an individual does has negligible impact on the whole economy, but what the government does – because of the scale of its expenditure – is very different. The crucial fact is that if the household and corporate sectors are very roughly in balance – i.e. neither net borrowers nor net lenders on a very major scale – the government deficit has to be more or less the same size as the foreign payments deficit. That is roughly the position shown in Table 2. Unless the private sector financial balance can be squeezed, for the government deficit to be reduced, the overseas deficit has to fall also – and vice versa.

If the government pursues austerity to try to reduce its deficit then to the extent that it succeeds, this may well reduce the current account deficit but the channel through which this would happen is by reduced aggregate demand cutting back the demand for imports.

Equally, a spontaneous improvement in the financial position of the private sector – perhaps through reduced consumption or investment – would lower the current account deficit but again by reducing aggregate demand and cutting back on demand for imports. But this would hardly count as an advance! Quite apart from causing a waste of economic potential, it would worsen the government’s deficit.

What is needed to improve both the current account balance and the government’s financial position without necessitating damaging domestic adjustments is something in the overseas sector itself – an improvement in the terms of trade, an increase in world demand for our exports, or a lower exchange rate. Of course, the UK has no control, or even much influence, over the first two of these. But it most assuredly does over the third.

If the UK were to enjoy a boost to its net exports (for whatever reason), then the current account deficit would fall and the government deficit would drop, thanks to increased tax receipts and lower government expenditure caused by a higher level of economic activity. Moreover, other things being equal, the financial position of the private sector would improve (as savings rose, thanks to higher income for both households and companies).

The unsustainability of consumer spending

The last serious imbalance in the UK economy is that far too much of what additional demand there has been – even though this has pushed up the growth rate and reduced unemployment – has been the result of increased consumption, which is itself unsustainable. As well as the increase in employment levels (which has raised total income from employment), the extra demand has been fed by increased consumer confidence, an explosion in credit, and a rise in asset prices. Over the period 2000 to 2015, house prices nationally have risen by 140% and in London by 200%. Meanwhile, the increases since 2009 have been 26% and 68% respectively, while between 2009 and 2015 the FTSE 100 index rose by 40%.

The European dimension

It is possible to overdo the gloom and doom about the UK’s trading position. After all, a significant part of the problem derives from the weakness of the eurozone, which is still overwhelmingly our largest single trading partner. Indeed, over the last four years, our trade with non-euro countries has improved considerably, to the point where it is now running at a substantial surplus. The overall trade account is only in deficit because we have been running a large and increasing deficit with the eurozone.

There may be certain long-term structural factors that make such a state of affairs – i.e. a deficit with the eurozone and a surplus with the rest of the world – the natural order of things. Even so, two factors have worsened the situation. First, the eurozone has grown extremely slowly compared to most other parts of the world, and certainly compared to the UK. This has limited the growth of its imports – including goods and services produced in the UK.

Indeed, estimates by Capital Economics suggest that if the eurozone had grown in line with the US and the UK then UK exports would have been boosted so much that, other things being equal, the UK could actually now be running an overall trade surplus.

This can be taken encouragingly. After all, if the eurozone returned to rude economic health, the UK might well be able to see a significant trade surplus without needing a lower exchange rate. On the other hand, there is scant prospect of this happening any time soon. Accordingly, UK economic policy has to take the eurozone as it is and this implies the need for a lower exchange rate to generate a much improved trade performance.

Second, although the ECB was slow to adopt a policy of quantitative easing (QE), and slow also to cut interest rates, more recently it has been more overtly expansionary with regard to both interest rates and QE. Given the limited effectiveness of QE operating through the usual domestic channels, this policy has been widely interpreted as a competitive exchange rate strategy. Between January 2007 and February 2016, before Brexit fears really began to build, the pound/euro exchange rate rose by 11%. With the UK growing strongly and not operating any sort of exchange rate policy, this has contributed a substantial amount to the eurozone’s recovery. Indeed, its strategy has relied on taking business from the UK, in the eurozone, the UK and third parties. This is indeed a classic case of beggar thy neighbour. And in this instance we are the neighbour. The UK is in sore need of a new policy.

The optimal current account position

In all the discussions about UK economic policy we cannot recall any consideration – in the public or private sector – of what the optimal current account balance is for a country such as the UK. It is widely assumed that about zero is about right – although it seems also to arouse scant anxiety that the UK balance has been nowhere near this point for a long time.

Moreover, plenty of other developed economies are nowhere near it either. Germany is running a current account surplus of 8% of GDP, while the figures for Norway and Switzerland are 6.9% and 7.2% respectively. Although China’s surplus has fallen a long way, it is still running at 3% of GDP. Japan’s surplus is also 3% of GDP, while Singapore’s is a staggering 20% of GDP. Of course, there must also be some substantial deficits to balance these surpluses – and there are. Besides the UK with its deficit of 5.4% in 2015, the US has a deficit of 2.6% and many countries in Africa and Latin America are running large deficits.

Thinking about the developed countries such as Germany, Switzerland, and Singapore, are they so different from the UK that their optimal current account position is radically different from the UK’s? And if not, whose is out of kilter: theirs or the UK’s? Or both?

The current account and wealth accumulation

The starting point for an analysis of this issue is the realisation that the current account position reflects the difference between national saving and investment. A surplus reflects an excess of domestic saving over domestic investment while a deficit reflects a shortfall. Equally, a current account surplus, as a matter of logic, always has as its counterpart a capital account deficit, that is to say, a flow of capital abroad. Accordingly, other things equal, a current account surplus adds to the stock of national wealth (in the form of real assets abroad, or financial claims on other countries) and a deficit diminishes it (as overseas holdings of real assets or claims on the country increase).

Whether a country should run a surplus or deficit therefore comes down to a decision about the optimum rate of investment (and capital accumulation) and the balance of advantages and disadvantages about having this desired level, whatever it is, financed domestically or by overseas wealth holders, as well as the balance of advantages and disadvantages from accumulating wealth in the form of real assets or paper claims on foreigners as opposed to real assets at home.

The Chinese case

China may provide a useful starting point. It has both a huge level of investment, and a huge level of saving, both close to 50% of GDP, but saving has run ahead of investment, reflected in the current account surplus. It is widely believed that China’s investment rate is excessive in that much of the investment is wasteful and the poor returns on it threaten the stability of the banking system.

But if China reduced investment, other things equal, this would both reduce aggregate demand and cause the current account surplus to widen. What China’s economy appears to need is reduced saving and increased consumption, both to make up for reduced investment and to close the current account gap. Why is this not the policy of the Chinese authorities? To some extent it is, certainly in their rhetoric. And China’s surplus has fallen substantially. But the authorities are concerned to move slowly in case a collapse of investment causes a hard landing in the economy. Nevertheless, there is a suspicion that elements within the authorities have decided that a continued surplus is in China’s interest. They may believe that:

- Having a strong export sector, building up surpluses, furthers the long-term growth of China’s economy;

- Amassing huge foreign exchange reserves puts China in a strong bargaining position vis-vis the rest of the world and gives the Chinese government substantial international clout;

- The huge reserves protect China and its currency from possible instability in the future.

While conceding somewhat on point (iii), most western analysts find China’s continued surplus bizarre. Essentially it involves still poor Chinese people saving (i.e. not consuming) in order to allow rich Americans (and others) to spend and consume.

Demographics

Demographic considerations also have a considerable influence on the optimum current account position. Suppose that a country’s population is set to age substantially. When this happens, you would expect a substantial swing towards dis-saving as retirees carry on spending even though they are no longer working and producing. In anticipation of this situation, it would be prudent for the country as a whole to build up financial assets through saving. This would take the form of persistent current account surpluses, implying the build-up of net overseas assets. So a country about to undergo a significant ageing of its population might readily run a significant current account surplus at first, counter-balanced subsequently by a significant current account deficit as retirees spend their accumulated capital.

The demographic factor has been a widely used argument to justify Japan’s sustained current account surplus. It is sometimes also deployed to justify Germany’s and Switzerland’s (although it is unclear how well such an argument stands up in their case).

The UK has strong demographics, with the population set to grow considerably. Nevertheless, this cannot justify more than a fraction of the UK’s current account deficit.

The UK case

Turning to the UK in more detail, in marked contrast to China, we appear to have an inadequate rate of domestic investment which is not fully funded by domestic saving, hence the current account deficit. Indeed, it is the low rate of saving that is the appropriate marker because the need to draw in savings from abroad to finance such investment as we carry out, reduces the effective rate of capital accumulation, since part of whatever is accumulated is owned, or at least claimed against, by overseas wealth holders.

It is easy to get yourself in a pickle by agonising about the direction of causation behind the accounting identities. Is it low saving that ‘causes’ the current account deficit, or the current account deficit (i.e. the excess of imports over exports) that causes low saving (because it depresses incomes)? In reality, the relationships are symbiotic. The causation is complex, different between countries and may change over time. But we need not agonise about these complexities.

As regards what needs to change to bring about a satisfactory macroeconomic result for the UK in current circumstances there is no doubt. The last thing we need is to reduce investment, while increased saving (either or both of which would reduce the current account deficit) would, other things equal, reduce aggregate demand and increase unemployment. What is required is a set of policies that reduce or eliminate the current account deficit without depressing aggregate demand.

That means a lower exchange rate than we have been used to – at least until the Brexit vote caused it to drop. Higher exports and/or lower imports would not only reduce the current account deficit but, assuming that there are spare resources in the economy, would also raise GDP and income and hence increase private savings, as well as reducing the fiscal deficit.

No subject for government?

There is a view that, aside from the contribution of their own fiscal policy, governments should take no interest in the current account. The private sector’s current account balance is a private matter and governments should leave well alone. Accordingly, if a country runs a current account deficit while the public financial position is balanced – that is to say the current account position is wholly private – then the government should not turn a hair. It is simply none of its business. After all, such a private sector deficit represents the profit and utility maximising decisions of countless ‘economic agents’ who, acting in their own personal best interests, produce an outcome that is the best possible one for them, given the prevailing circumstances.

Putting the matter slightly differently, with regard to just about all other markets, most economists believe that markets are best left to their own devices. The market prices that are the result of the forces of supply and demand produce the best possible outcome for production and welfare, given the prevailing circumstances. Why should the foreign exchange market be any different?

This argument that balance of payments imbalances don’t matter and the foreign exchange market should be left to its own devices is unconvincing:

- Significant current account deficits often do occur side by side with substantial public deficits (this is currently true in the UK, but this is not always the case);

- Private sector ‘agents’ take their decisions, including decisions about overseas transactions that then affect the exchange rate, in the context of a panoply of policies set by the government (and central bank);

- It is widely acknowledged that with regard to saving and investment, the private sector cannot always be relied upon to take decisions which are in its best interests. Because of the separation of ownership from control, managements of business enterprises may invest significantly too little. Meanwhile, in regard to their saving behaviour, individuals are notably myopic;

- There is no necessary reason why the self-interested decisions of international asset holders should coincide with our national self-interest;

- There is ample evidence that real exchange rates can diverge from the underlying fundamentals for long periods and ample evidence that such divergences can do huge damage;

- The foreign exchange market is different from most other markets because investors and traders do not have a clear view of what the right level is for an exchange rate, and because a misaligned exchange rate can have huge effects on the economy, which then affect the appropriate level of the exchange rate;

- If ‘countries’ mean anything at all, then governments have a responsibility that goes beyond the self-interest of today’s ‘economic agents’. If they don’t, then what is the point of so much economic policy? If current account deficits do no matter as long as they are ‘private’, in what sense is it right for governments to strive to boost the rate of economic growth? Why not simply leave it to be determined as the outcome of ‘market forces’?

Conclusion

The upshot is that although it might be extremely difficult to pin down the size of the optimum current account surplus or deficit, in the UK’s case we may be pretty sure that its current huge deficit is seriously sub-optimal. What’s more, bearing in mind the consequences for both the real economy and the financial markets, this is most assuredly something for the policy authorities to be concerned about. Indeed, we suspect that there is scarcely any other country in the developed world (apart possibly from the US, which is a special case) that would have regarded its exchange rate and balance of payments with such blithe insouciance.

This essay is an edited extract from the book The Real Sterling Crisis: Why the UK needs a policy to keep the exchange rate down, which is available here.