The impending economic disaster and the pound’s role in causing it

Roger Bootle and John Mills, September 2016

Many people in the market and much of the commentariat are currently concerned with the recent weakness of the pound on the exchanges. They are barking up the wrong tree. The real sterling crisis is that the pound has been too high.

Many people in the market and much of the commentariat are currently concerned with the recent weakness of the pound on the exchanges. They are barking up the wrong tree. The real sterling crisis is that the pound has been too high.

Accordingly, the Brexit-inspired bout of sterling weakness was extremely good news for the British economy. Far from panicking about the lower pound, the UK authorities should be concerning themselves with the question of how they can ensure that the pound continues to trade at a competitive level in the future.

The exchange rate of the pound is vital to the success and health of the UK economy and the fact that it has long been stuck at much too high a level bears much of the responsibility for the economy’s current ills. These results have not exactly been intended. Despite the exchange rate’s importance for the UK, for almost 25 years there has been no policy for it. As a policy variable the pound has been left in a state of neglect, in the belief that other things (principally inflation) should determine policy, and/or because ‘the markets know best’. This latter belief mirrors the establishment’s faith in the financial markets prior to the crisis of 2008/9.

But we have subsequently learned, if we did not know it beforehand, that, left to their own devices, the financial markets may systematically misprice financial variables, and that they may behave in a reckless way in the pursuit of individual short-term gain that puts the long-term stability of the financial system at risk.

Interestingly, although such reasoning is now widely accepted in relation to the equity and property markets, recently no one seems to have made these points about foreign exchange markets – until now. This would be surprising to an earlier generation of economists schooled in the crises and policy disputes of the 1930s. They were brought up to believe that, not only could markets malfunction dramatically, but they could produce and sustain a destabilising set of exchange rates, which could have devastating consequences for the real economy.

No one was more aware of the importance of exchange rates than John Maynard Keynes. In the 1930s, a series of devaluations and the imposition of protectionist trade policies were major contributors to the Great Depression. Following that experience, Keynes was determined to establish for the post-war world a global exchange rate regime that placed equal obligations on deficit and surplus countries to adjust, thereby ensuring that the new system did not have a deflationary bias.

This is most definitely not the system that we have today. Rather, financial pressures to adjust are felt by deficit countries, while surplus countries, such as China, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland, feel very little pressure at all. The result is a deflationary tendency for the world as a whole – felt particularly strongly within the eurozone. The UK is not part of this deflationary tendency – although we suffer from its consequences. And we do suffer acutely from exchange rate misalignment. There has been a deep-seated tendency for sterling to settle at too high a level for the health of the UK economy.

This is for two main reasons. First, because of the UK’s political stability and the extraordinary liquidity and attractions of its asset markets, it has a decided tendency to attract private capital flows that push up the real exchange rate. Second, because of a history of inherently strong domestic inflationary pressure, the UK policy authorities have tended to welcome, and even encourage, a strong exchange rate as a way of bearing down on UK inflation.

The results are devastating. On the financial side, persistent current account deficits undermine the country’s financial future. The UK is now a substantial net debtor. Excessive borrowing would be bad enough but the UK has increasingly sold real assets. The result is that not only is the present borrowing from the future, but there is also a loss of national control over important parts of the economy. This weak external position particularly affects our manufacturing sector, bolstering the forces making for its decline as a share of GDP. This then diminishes our prospective rate of productivity growth (since productivity growth is stronger in manufacturing than services), intensifies the problems associated with employing lower skilled workers, increases inequality, and accentuates the regional divide.

Accordingly, an economic policy that accorded a much greater role for the exchange rate would potentially bring significant benefits. As things stand, however, we do not have a free hand in adopting an exchange rate policy. The G7 specifically forbids the deliberate manipulation of exchange rates to gain competitive advantage. Mind you, this has not stopped Japan and the eurozone following closet policies of exchange rate depreciation. Outside the G7, China and Switzerland, among umpteen others, have put the management of the exchange rate centre-stage. By contrast, as so often, the UK authorities are left playing ‘goody two shoes’.

There are ways in which the UK could adhere to its formal G7 commitments while effectively pursuing a policy that puts the maintenance of a competitive exchange rate centre-stage. These include putting less reliance on a policy of high interest rates. Continued fiscal stringency plus use of the Bank of England’s Prudential Policy toolkit offers a way of doing this. In addition, measures could be taken to make UK real assets less attractive to foreigners.

Of course, we recognise that competitive devaluation is a zero sum game. Any attempt by the UK to gain competitiveness through a lower exchange rate could be nullified if other countries followed suit. In practice, in current conditions, when the UK is now only a medium-sized player in the world economy, direct retaliation on any scale is not likely. Moreover, the UK has been a loser from other countries’ depreciations – including by the eurozone. It would not be a case of the UK trying to boost its economy by following a mercantilist prescription in order to increase its exports. The key point is that the UK is running a very large current account deficit.

A change of policy regime to give greater weight to the exchange rate would necessarily involve some changes to the current inflation targeting regime. But that need not constitute a barrier. Inflation targets are not the last word in macroeconomic policy and plenty of other countries do not allow their policy to be completely dominated by inflation concerns. But it should be possible to fashion a policy regime which retains inflation targets while giving significant weight to the exchange rate. Ideally, the world should move towards a new international policy regime that puts exchange rates centre stage and seeks to maintain exchange rates at a reasonable level in relation to the economic fundamentals. But the UK cannot wait for this to happen.

With the British people having voted to leave the EU, this is an ideal time for the British government to pursue an alternative policy framework. Indeed, setting a policy that would establish and maintain a competitive exchange rate for sterling is the single most important thing that a government can do for the promotion of a prosperous Britain.

The impending economic disaster and the pound’s role in causing it

Unless something changes, the UK economy is heading for the rocks. This is not because of the consequences of Brexit. On the contrary, the factors that we identify in The Real Sterling Crisis that cause us such unease predate Brexit, or even the chance of it, and have practically nothing to do with it.

On the face of it, the British economy does not look too bad. But we are not paying our way in the world. Every year, we are borrowing and selling assets to the tune of about 5% of GDP. This is rapidly increasing the amount of our economy that is owned by foreigners. This would not matter so much if we were using the money provided by foreigners to invest in productive capacity. But we are not. UK investment is extremely low. We are borrowing and selling assets in order to maintain our standard of consumption.

If things continue as at present then in 10 years’ time we will have transferred to foreigners assets and ownership of assets amounting to 50% of one year’s GDP. With this transfer goes a stream of income, paid to foreigners, out of what we produce in the UK. This will mean that for any given level of what we produce here in the UK (GDP), less will be available to be enjoyed by UK citizens. And if, as at present, foreign wealth holders buy UK real assets, along with the financial transfer goes a substantial amount of control over our economy.

At a time of low interest rates, as at present, the cost of being a net debtor is relatively low. But eventually, of course, interest rates will rise. At that point the cost of the UK being a net debtor would be much higher than at present. Accordingly, the UK could be storing up a problem for the future much larger than it currently imagines. This outturn would be bad enough if the alternative were to squeeze our living standards now in order to protect and preserve our financial position and the level of our living standards in future. But this is not the situation. Our failure to pay our way derives from the weakness of net exports. Our economy is still operating a substantial way below full capacity. In that case, it should be possible to increase net exports and boost GDP. In other words, the thing that is hurting our living standards in future, is also reducing our incomes today. If we were able to increase our net exports this would not only boost incomes and employment but it would do so in parts of the economy that have recently done relatively badly – the parts that have been heavily dependent upon manufacturing, thereby helping to address some of our country’s problems with inequality.

Moreover, there are links between the current account deficit and the UK’s other serious deficit, namely the fiscal one. The financial balance of the UK private sector, UK public sector and the overseas sector must sum to zero. Accordingly, if the government tries to improve its financial position (i.e. the gap between expenditure and tax revenue) without there being an improvement in Britain’s overseas balance, then this can only happen through a worsening of the private sector financial balance, which is often difficult to achieve. Another way of putting this is that policies of austerity often fail. By contrast, a spontaneous improvement in the current account of the balance of payments would usually improve the financial balance of both the public and private sectors. Higher incomes (from net exports) would automatically improve the financial balance of the private sector and, as they pay taxes on this income (and receive fewer state benefits because of increased income) the public deficit will fall.

The role of the exchange rate

There is more than one reason for our country’s weak position on the balance of its overseas income and expenditure (the current account of the balance of payments). Moreover, there is a plethora of problems in the British economy that are not directly connected with the weakness of our balance of payments and cannot be addressed by changes in the value of the currency. Real lasting economic success, and successful dealings with other countries, depend upon building real competitive advantages that are difficult to replicate. Nevertheless, these real factors are difficult to change in the short term. Moreover, sometimes the exchange rate can be stuck at the wrong level and this can be a source of severe difficulty, even if the ‘real’ sources of competitive advantage are set favourably.

It is our contention that too high a level of the pound on the foreign exchanges – the exchange rate against other currencies – is a leading cause of the UK’s large current account deficit and that this has major adverse consequences for our economy. Quite simply, for countries heavily engaged in international trade, as the UK is, the exchange rate is the most important price in the economy. Too high a level of the pound will tend to restrict our exports (by making them more expensive) and stimulate imports (by making them cheaper).

Moreover, the exchange rate has a critical bearing on another crucial variable – the profit rate. Other things equal, a higher exchange rate reduces profits and boosts real wages and the real value of other sources of consumer income. Reduced profits tend to lead to lower investment – and lower investment leads to weaker growth and hence lower living standards in future. But the squeeze on profits is not uniform across the economy. On the contrary, it will be felt by industries engaged in exporting and/or competing with imports. We refer to exports of goods and services, goods and services that would be exported, imports of goods and services, and goods and services that could be imported, as tradables.

A high exchange rate diminishes the price of tradables relative to non-tradables, and thereby diminishes the profit rate of industries producing tradables relative to those producing non-tradables. Furthermore, an exchange rate that undergoes substantial fluctuations will cause substantial fluctuations in the profit rate in industries that produce tradables. This variability will diminish the attractions of investment in tradable industries.

Accordingly, an exchange rate that is too high for extended periods will tend to lead to an unbalanced economy – with too small a manufacturing sector. It is our contention that this is exactly what has happened in the UK.

It is often argued that the UK’s problems with its external trade – and hence with its manufacturing industry – originate with real factors, such as the rise of China, that have little, if anything, to do with the exchange rate. Such views are partly justified, and partly dangerous nonsense. The UK steel industry has recently faced an existential crisis which is widely

blamed on the cheapness of steel production in the emerging markets, especially China. In fact, in 2014 the UK imported more than four times as much steel from the EU as from the whole of Asia. The exchange rate is seriously relevant to this.

What is the right value for the pound?

By how much is the pound over-valued? Or is it, post-Brexit, now at the right level? There is no hard and fast answer, but we can begin to make some suggestions about orders of magnitude. First, we can track movements in the real effective exchange rate, that is to say, the pound’s average value, once account is taken of movements in costs and prices in different countries.

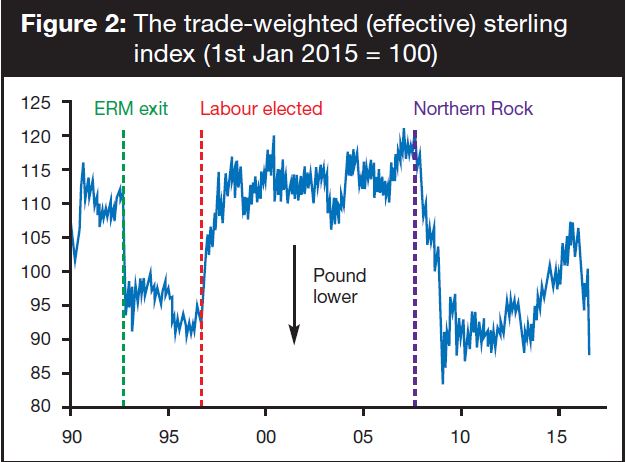

When trying to gauge how over– or under-valued a currency is, it is important not to be fixated upon the exchange rate against one particular currency. The most likely candidate for such currency fixation is the dollar. Yet the UK does much more of its trade with countries that don’t use the dollar, with the eurozone being the most important. Accordingly, the best way to measure the value of the pound is to take the average of its value against the currencies used in British trade, with the weight of each currency in the basket governed by the weight of that currency in Britain’s overall trade. The measure that does this is the trade-weighted index of the pound, sometimes known as the effective index of the pound.

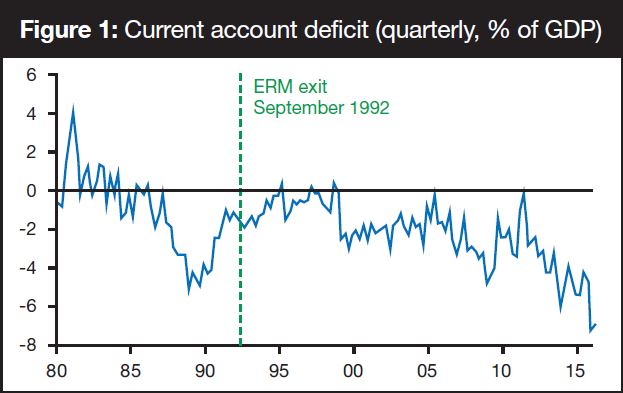

Yet it is important not to be fixated by the nominal value of this index. A country’s price competitiveness is governed by the relationship between the value of its currency and the level of domestic costs and prices compared to costs and prices abroad. For instance, if a country undergoes a 10% fall in its currency but also experiences a 10% rise in its costs and prices relative to those abroad, then its price competitiveness will not have changed. Accordingly, to measure changes in price competitiveness economists usually focus on the real exchange rate, that is to say the nominal rate adjusted for changes in relative costs and prices across countries. Even when these two adjustments are made, judging by how much a currency may be over-valued is more of an art than a science. But we can have a stab at coming to an answer. As Figure 1 shows, the last time that the UK ran a tolerably low current account deficit was in the period immediately after the pound’s ejection from the ERM in September 1992. This provides a guide to what should be a competitive exchange rate for the UK.

It suggests that on the Bank of England’s measure of the pound’s average value, the so-called effective exchange rate, the pound should probably be somewhere close to 75-80, compared to 100 in 2005. But as Figure 2 shows, starting just before the election of the Labour government in 1997, and continuing afterwards, the pound rose sharply. There followed a 10-year period of rough stability – but stability at too high a level. Indeed, during this period the pound was at roughly the same level that it had been at prior to it being forced out of the ERM in September 1992. (The history of the real exchange rate over this period is very close to the nominal rate.)

Its value took a dramatic dive immediately after the financial crisis in 2008/9, which returned its value roughly to where it had been in the immediate wake of the ERM crisis – and at one brief point even lower. After that, however, the effective exchange rate of the pound rose. At its recent peak in November 2015, it stood 30% above the trough reached in March 2009. After the Brexit-inspired drop, in early July, the exchange rate stood roughly where it was after the ERM exit, and slightly above the trough that it reached after the financial crisis in 2009. Something like this may be the right level for the UK to rebalance its economy.

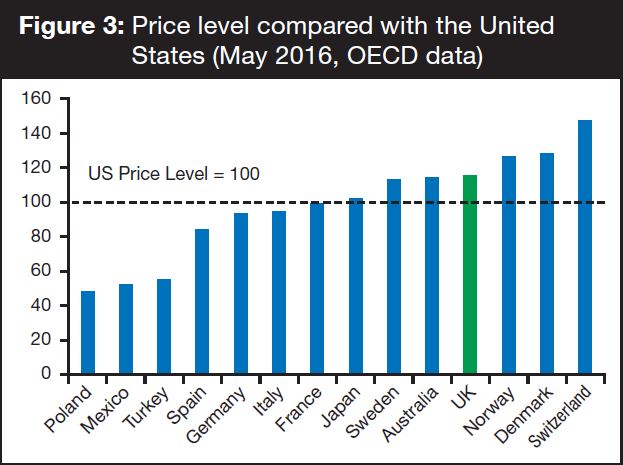

We can also draw on the evidence of direct price comparisons. To make a more general assessment of whether prices are high or low in the UK it is useful to compare prices to those in several other countries. Figure 3 shows comparative price levels for various OECD countries. These data are for May 2016.

This chart fits with conventional wisdom. For example, it shows that prices in the UK are generally much higher than in much poorer economies such as Poland, Mexico and Turkey. It also shows that prices in the UK are much lower than in Switzerland, Denmark and Norway. Less obviously, Figure 3 suggests that in May the general price level was higher in the UK than in most other advanced economies. For example, it was 15% higher in the UK than in the US; 16% higher than in France; 13% higher than in Japan; and 24% higher than in Germany. At face value, this suggests that the pound was over-valued. The fall of the pound after the Brexit vote will have altered these figures considerably After the Brexit-inspired fall of the pound, it was trading at a competitive level that hadn’t been experienced for many years. We believe that this will prove to be an extremely good thing for the UK economy.

This essay is an edited extract from the book The Real Sterling Crisis: Why the UK needs a policy to keep the exchange rate down, which is available here.