Why have we built so few homes on surplus public sector land?

Daniel Bentley, 20 July 2016

In his first outing in the Commons as Communities and Local Government Secretary this week, Sajid Javid described the green belt as “absolutely sacrosanct”. He was only reiterating the position of the new prime minister, Theresa May, on this subject but he was more than happy to drive the point home. This will anger a lot of housing campaigners. But, assuming that that position will not change, it places an even greater onus on the government to show that non-green belt land can yield the homes the country needs. There are many angles to this, of course, but one objective which has been crying out for a smarter approach for some time has been the utilisation of surplus public sector land.

The London Land Commission has estimated that there is surplus land enough in the capital alone to build at least 130,000 homes. Savills, the estate agency, has suggested there is enough in England for 2 million homes. These are substantial amounts of land which, given that they are in public ownership already, could be used to grease the wheels of housebuilding. Up to now, however, this has not been done in any meaningful way.

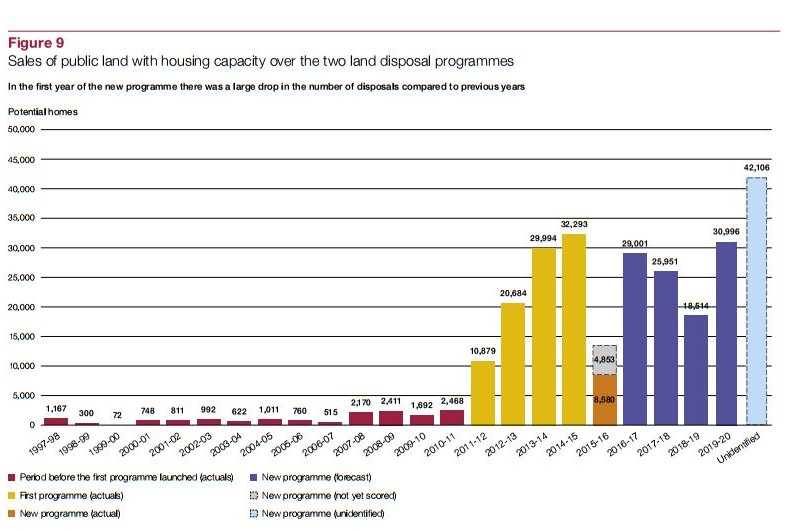

To be fair, the government has been alive to the potential in this area for some time. The Coalition promised in 2011 to sell off enough public sector land for 100,000 new homes by 2015. The new Cameron government last year promised to sell enough for another 160,000 by 2020, matched by local authorities releasing land for another 160,000. This is vastly more ambitious than under the 1997-2010 Labour government, as the following graph from the National Audit Office shows. But, coming to just over 400,000 homes, these are still not awfully large figures, given the amount of surplus public land that is thought to be out there.

Source: National Audit Office, ‘Disposal of public land for new homes: a progress report’, July 2016

Not only that but even releasing these sites for housebuilding is proving to be really quite a challenge. The 100,000 target during the 2010 parliament was achieved; in fact land for 109,950 homes was disposed of by 2015. But this included 15,740 from sales dating back as far as 1997 that had already been made, and another 10,000 from land that was by then already private sector (from the privatisation of Royal Mail and British Waterways).

This appears to have been the low-hanging fruit, however. A report by the National Audit Office last week revealed that progress on the 2015-2020 leg of this journey is proceeding very, very slowly indeed. Against a commitment to dispose of public sector land for 160,000 homes, only enough land for 8,580 was sold in the first 10 months of the new parliament. Enough for another 4,853 homes has been sold too but it it not clear yet whether that will actually be used for housing; assuming that it is, that would still only be 8 per cent of the way towards the target.

Worse still, land for only another 104,461 homes has even been identified for sale. And half of that – worth 54,832 homes – has issues outstanding meaning it is ‘very unlikely’ to be sold by 2020. All in all, the government is currently on course to sell off land for approximately 63,000 homes by the end of the parliament.

Why is this process so tough? Partly it is because, as Savills pointed out in its 2014 analysis, there is a lack of data about what the public sector owns and where; there is not enough transparency. The London Land Commission Register, which was published in January and maps all the publicly-owned land in the capital, is a major breakthrough in this respect, albeit limited to London.

Another problem is that public sector bodies succumb to the same temptations as private landowners when it comes to selling off their holdings; that is to say, it often pays to hold on a bit longer before selling. Whitehall guidance effectively encourages this, advising that departments should not hold on to land longer than necessary but at the same time urging that a sale ‘provides value for the taxpayer’; in a rising market there is no better way of extracting additional value from land than to sit on it. On top of that, there is simply not the urgency or priority placed on these matters in individual government departments.

These issues come together to create an almighty headache for whoever in Whitehall is placed in charge of identifying land that should be used for homes. This was eloquently expressed by the man who not so long ago had precisely that job, Lord (Bob) Kerslake, the former head of civil service and permanent secretary at the Department for Communities and Local Government. He told the Lords Economic Affairs Committee recently:

I led the programme to identify public land for disposal across government and it was an immensely tough process. Basically, this is not the priority for any individual department, so you have to persuade, cajole and threaten them to release this land and get on with it… Often, the issue is not people being resistant to it; it is that it is not as important to them as it is to us and they lack the capacity. This is particularly true in the Health Service, where you have major hospitals, often with huge amounts of land, which lack the capacity to bring forward the sites for development.

Persuade, cajole and threaten. To overcome these problems, the Lords Economic Affairs Committee recommended that a senior Cabinet minister be put in charge of coordinating the release of public land for housing, and that the requirement to achieve best market value should be relaxed.

But then there is a further challenge which might be even greater than identifying and selling off the land: getting it built out. This is illustrated by the abysmal rate of development on public sector land sold off during the last parliament. DCLG estimated earlier this year that only a fraction of the 109,590 homes had even been started. When it looked at a sample of 100 sites, with estimated capacity for 8,600 homes, just 200 (2 per cent) homes had been completed and 2,200 (26 per cent) started. Extrapolated across the whole programme it would suggest that only a few thousand homes had actually been built.

This is a waste of public resources which ought to be put to much greater use. It would make more sense to directly commission this work in such a way that progress is determined by the government rather than selling the land to private developers who then take their time building it out. This would present an opportunity to get smaller housebuilders involved, for whom the price of the land is usually a barrier to entry. The government has already embarked on some direct commissioning recently (for exactly these reasons), but on a very small scale – for just 13,000 homes. More of this – a lot more – might be a good idea.

Daniel Bentley is editorial director of Civitas and the author of The Housing Question: Overcoming the shortage of homes. He tweets @danielbentley