Rising household debt – should we be worried?

Daniel Bentley, 13 February 2018

A decade on from the financial crisis, household debt relative to income is almost as high as it has ever been. After several years of deleveraging, since 2015 mortgage lending and especially consumer credit have begun to rise again. The debt-to-income ratio reached 138 per cent at the end of last year. This is lower than the 156 per cent peak in 2008 but, as the Resolution Foundation shows in an excellent new report, this remains significantly higher than the 1988-2002 average of 97 per cent. Indeed, the Office for Budget Responsibility projects that this ratio will rise to about 150 per cent in 2023. So there has been no major readjustment in levels of indebtedness, and it now seems set to drift back to levels on the eve of the crisis.

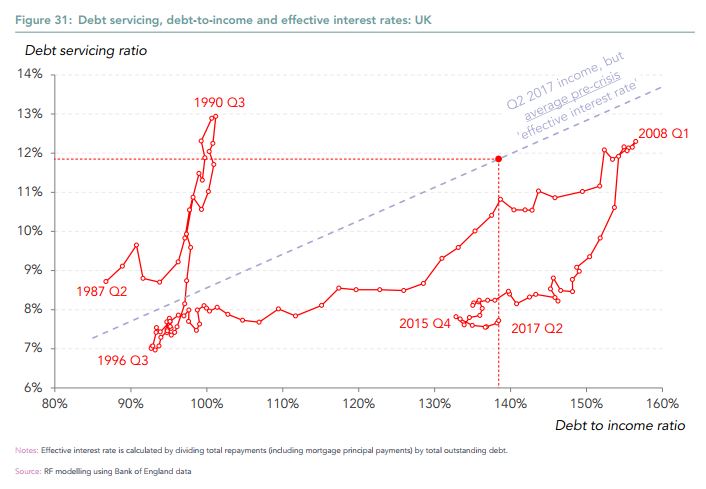

The big difference between now and then of course is the cost of servicing loans. Interest rates being much lower today, debt repayments were down from 12.3 per cent of household income in 2008 to just 7.7 per cent in 2017. So while borrowing is still around mid-2000s levels, the pressure on household finances is not as great as it was. The following graph captures this well:

If interest rates were to quickly ‘normalise’, this level of debt would be much more problematic. The Bank of England signalled just last week that a series of interest rate rises is on the way, but still they are not expected to return to pre-crisis levels. No need for alarm just yet, then. In addition to the low debt-servicing ratios, we might also take some comfort from the regulatory reforms that have been introduced since the crisis, which have removed or reduced some of the riskier lending practices such as self-certification and very high loan-to-value multiples. Taking all of this together, the Resolution Foundation describes the household debt position as ‘relatively healthy’ – notwithstanding a significant minority of mostly lower-income households who are showing signs of debt ‘distress’.

However, there is a deeper issue that arises for the economy when households are highly indebted, even if we are confident that borrowers are capable of repaying their loans. When debt builds up relative to incomes, this can greatly increase the severity of any economic downturn. As the economists Atif Mian and Amir Sufi explain in their 2014 book House of Debt, high levels of household debt generate especially severe recessions because the more leveraged households are, the more they are likely to cut back spending in a downturn. This is largely to do with the spending habits of homeowners: when their property increases in value and their net wealth rises, they spend more (including taking out more unsecured debt to spend on consumer goods), but when it decreases they feel less wealthy and consume less. ‘The relation between elevated household debt, asset-price collapses, and severe contractions is ironclad,’ Mian and Sufi write.

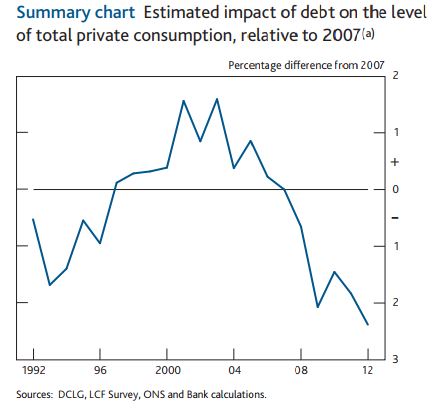

Similarly a Bank of England paper from 2014 describes how relatively high debt levels in the UK increased the severity of the recession here by causing a greater decline in consumption than otherwise would have been the case. Philip Bunn and May Rostom showed how households with higher levels of mortgage debt cut their spending by more, on average, in the years following the crisis. Highly indebted households, having spent proportionately more of their incomes on non-housing consumption before the crisis, then cut that spending even more severely after the crisis. Bunn and Rostom estimated that this effect accounted for two percentage points of the five per cent total fall in aggregate private consumption after 2007. That two per cent had still not returned by 2012 (the latest year for which there was data when they undertook their analysis). This is illustrated in the following chart:

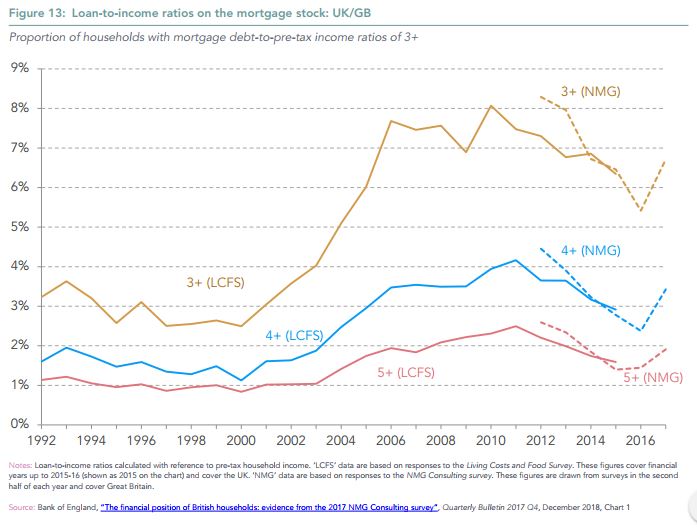

These adjusted spending levels were larger the higher the debt level of the household, even controlling for other factors. The effect was modest for those with debt-to-income ratios below two; it was highest among those with a ratio above four. This brings us back to the Resolution Foundation’s report and data from the Bank of England from the end of last year. This showed that the proportion of households with loan-to-income ratios of three or higher, having tailed off since about 2010/11, has recently started rising once more and is possibly back to around 2006 levels, as the following graph shows. The proportion of new mortgages with a loan-to-income ratio greater than four has risen from 10.2 per cent at the beginning of 2016 to 28.3 per cent in the third quarter of 2017.

There are many fewer mortage-holders today – just 28 per cent of households in 2016/17, compared with about 40 per cent on the eve of the crisis, according to the English Household Survey. But this means that while the increase in mortgage lending proportionate to all household incomes looks quite modest, that debt is concentrated in fewer households. Many of those households are also spreading out their payments over considerably longer terms: the proportion of 30-year-plus mortgages almost trebling from from 12.6 per cent to 36.2 per cent between 2006 and 2017 (even 35-year terms have increased to 16.5 per cent). Not only does a longer term mean that the borrower pays more interest over the course of the loan, but in the initial years they are paying off significantly less capital and so they are remaining highly leveraged for longer.

None of this is to suggest that the UK is any more exposed to the risk of arrears and defaults. Quite the reverse – as the Resolution Foundation points out, much of this debt looks considerably safer now, and the banking system less vulnerable, than a decade ago. However, low debt-servicing ratios, due to continued low interest rates, may well be distracting from the discrete danger that nevertheless lies in high household indebtedness. The higher this is allowed to go, the more severely that indebted households are likely to pull back on spending if – or when – house prices fall and the economy turns down.

The Resolution Foundation report,’An unhealthy interest?’ by Matthew Whittaker, can be read here.