Should the Bank of England be responsible for controlling house prices?

Daniel Bentley, 11 April 2019

Labour is said to be considering whether the Bank of England should be mandated to limit house price growth. According to The Guardian, this would be done not via interest rates but via mortgage regulation as overseen by the financial policy committee (FPC). The FPC already curbs some mortgage lending, principally by capping loan-to-income ratios of more than 4.5 to just 15 per cent of new mortgages. But this is for financial stability reasons, rather than to temper house price growth.

John Healey, the shadow housing secretary, is considering whether the FPC’s remit should be extended to cover the latter. This raises two questions: Could it work? And, if it could, is it a good idea? Mr Healey is certainly right to be looking at demand-side reforms alongside the party’s ambitious supply-side ideas. When it comes to house prices, there is more that could be achieved, and quickly, using demand levers than there is using supply levers.

Nevertheless, each side of this equation influences prices to some degree and so this brings us to the first challenge: it would be tough on the Bank to expect it to control house price growth with only macroprudential tools. Without also being given responsibility for planning, capital build subsidies, and so on, it would be like trying to steer a boat with one oar.

This issue might be addressed in part by refining the mandate, however. Rather than being charged with keeping house price growth within a certain range, a more reasonable objective would be to cap the price-to-rent ratio. This is the measure that is important in terms of credit influencing house prices. While rents reflect the supply of housing versus the need for it (ie, as accommodation), prices reflect the investment value of buying a property that yields a given rent.

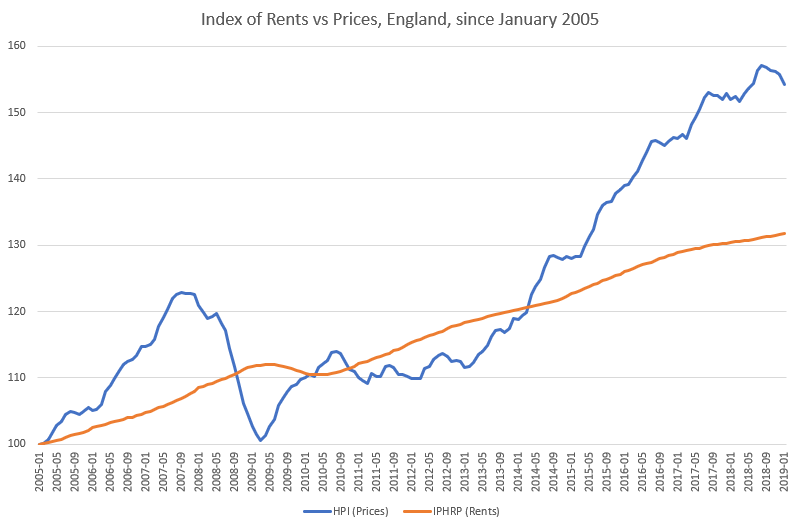

Prices have risen much faster than rents over the past 20 years due to the large increase in demand arising from a global fall in interest rates (the chart below only goes back as far as 2005, but even here the divergence between prices and rents in recent years is dramatic). Lower interest rates have not only given buyers (including owner-occupiers) the ability to borrow more for any given property, they have also encouraged investors to buy property in their search for a decent yield. Hence the rapid expansion of the private rented sector.

This brings us to a further challenge, however, in reducing or limiting even the price-to-rent ratio. Unless you think the UK housing market is in a bubble (and this is not the given that many take it for), the current price-to-rent ratio is simply a reflection of the current investment value of housing. That is, prices are justifiable for investors given the rental yield properties provide and the alternatives on offer elsewhere. The implication of this is that if you remove the ability of some people to borrow up to current prices, others who do not need to borrow (as much or at all) will simply buy those properties instead at the same or a similar price. In other words, you would be disadvantaging those with little capital and/or lower earnings – to the benefit of those with more capital and/or higher earnings.

So, is it a good idea? If tighter mortgage lending is intended for economic and financial stability, then that is possibly a good idea. There would be less borrowing against property, households would be less leveraged, and so banks and the wider economy would be less vulnerable in the event of a downturn or if interest rates rise suddenly. Such considerations are important and arguably still not given enough attention. But the Bank already has a financial stability remit, which could always be revised. A house price remit would be something different.

If the goal is to reduce house prices in order to improve the affordability of housing for first-time buyers – which is what it seems to be – then it is not so clear that tightening mortgage lending would have that result. To the extent that prices were reduced (which, as noted already, might not be by very much) this would likely be due to a decline in demand from those currently requiring high loan-to-value or loan-to-income mortgages… who are disproportionately prospective first-time buyers.

This disadvantage could of course be offset by other measures. We have one scheme in place already to mitigate the impact on first-time buyers of tighter mortgage conditions: Help to Buy equity loans were introduced for precisely this purpose. But this simply replaces one form of demand for another. The smarter move, if the idea is to improve access to owner-occupation, might be to look to fiscal policy. Raising taxes on property would be a surer way of reducing capital values over time (preferably, for everybody’s sake, not all at once) and could be more easily calibrated to support those currently struggling to buy.