GPs make patients suffer to protect inefficient local hospitals

The government’s proposals to eliminate excessive waiting from the NHS stand no realistic chance of succeeding, according to a new report from independent social-policy think-tank Civitas.

The target of a maximum 18-week delay from referral to treatment (RTT), to be achieved by December 2008, is an impossibility, given the lacklustre performance of some strategic health authorities (SHAs), primary care trusts (PCTs) and hospital trusts.

As the government and the Department of Health are coming to realise, the only long-term solution to this is not targets, but choice and competition. The obstacle is now the unwillingness of GPs to provide the necessary information to patients, out of a misplaced desire to protect the inefficient local healthcare system, including the nearest hospital.

In Why are we waiting?, James Gubb, Director of the Civitas Health Unit, shows how the Labour government has tried to deal with the massive NHS waiting list which it inherited, and ‘to move the NHS away from a culture of waiting to a culture of booking’.

The favoured approach has been the imposition of targets on all levels of the NHS: originally a 48-hour maximum wait for a GP appointment by 2004; a four-hour maximum wait in A&E prior to admission, transfer or discharge by 2004; a three-month maximum wait for an outpatient appointment by 2005 and a six-month maximum wait for an inpatient appointment by 2005.

All of these were, by and large, met, but at some cost. There is evidence of ‘gaming’ of the system: doing just what is necessary to meet the target, without necessarily doing what is best for the patient. The most notorious example of this has been the practice of keeping patients in ambulances until A&E departments are confident of being able to treat them within four hours of admission. Targets encourage complacency, as if there is nothing to aim for once they are met, in spite of the fact that in most developed countries it would be regarded as unthinkable to have to wait six months for an operation.

Clearing the patient pathway

But these earlier targets had a significant gap: between seeing the GP, getting a referral to a specialist, and getting admitted to hospital for treatment, there is the important stage of diagnostics. These were not included in the first targets, although the speed with which you progress towards your necessary treatment is dependent on the speed with which tests are carried out:

In April 2006, 203,114 people were waiting longer than 13 weeks for diagnostics, of whom 96,416 were waiting longer than 26 weeks. The figure included some 12,648 waiting for longer than 13 weeks for MRI scans and 2,488 for CT scans. Since then improvement has been registered – virtually no-one is now waiting longer than 13 weeks for a CT scan and just 169 were waiting longer than this for an MRI scan- but, as of October 2007, there were still 30,832 patients waiting longer than 26 weeks for diagnostics, of which 16,551 were waiting over a year.

In order to dislodge this bottleneck, the government committed itself, in the NHS Improvement Plan (2004), to reducing every patient’s pathway of referral to treatment (RTT) – the time between seeing the GP and going into hospital – to 18 weeks by the end of 2008. There is an interim target of 85% to be achieved by the end of March 2008, and now that this is looming – and is sure to be missed – Health Minister Ben Bradshaw has announced a ‘10% buffer zone’ – in other words the target has come down to 90% by December 2008.

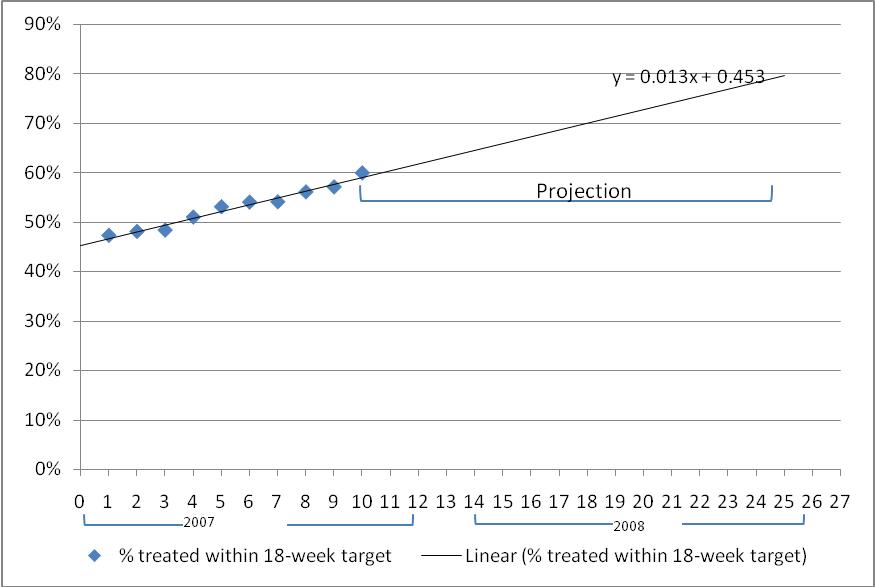

However, as James Gubb shows, there is no realistic possibility that this target will be met. When the target was announced, data were not even available to show how many patients were already on longer RTTs than 18 weeks. Since then, data have been collected, and there has certainly been an improvement. The latest count, September 2007, shows 57% of patients now receiving treatment within the 18-week target. What’s more, all the indications are that things are improving. In January 2007, only 47% of patients were making it through the pathway in this time; in April it was 51% and in June it was 54%.

However, thus far the trend improvement has been quite linear; if the same trend were to continue then by December 2008 around 77%, or roughly three-quarters, of patients will be turned around in 18 weeks – not 90%, and certainly not 100%. Clearly this also puts paid to the interim benchmark that 85% of admitted patients be treated within 18 weeks by March. Given current rates of improvement, this figure will stand around 65% – still a real achievement, but quite significantly off what is a very optimistic target.

Percentage of patients treated within 18 weeks of referral, England, January-September 2007 and projected improvement up to December 2008

Source: Department of Health (calculations by author)

Best and worst

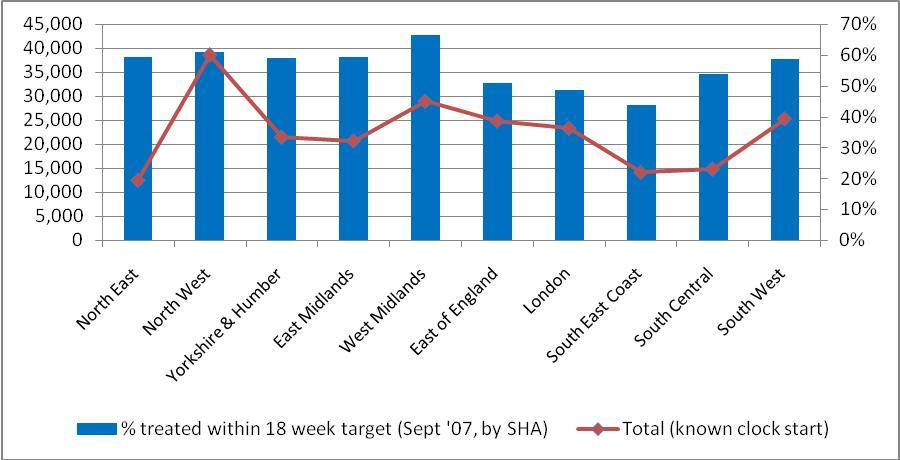

These figures are national averages and mask the true scale of the challenge. When we break the figures down by health authority and primary care trusts we uncover some truly bad performers; for these getting anywhere near 100% of patients treated within 18 weeks of referral looks nigh on impossible. In September 2007 the best and worst performers were as follows:

- Just 44% of elective referrals treated within 18 weeks in South East Coast Strategic Health Authority (SHA), compared with 67% in West Midlands SHA;

- Just 32% of elective referrals treated within 18 weeks in Brent Teaching Primary Care Trust (PCT) compared with 83% in Heart of Birmingham PCT;

- Just 23% of elective referrals treated within 18 weeks at West Hertfordshire NHS Trust compared with 88% in Yeovil District Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.*

- Just 26% of referrals for neurology treated within 18 weeks in East Midlands SHA, compared with 86% in North East SHA.

- In October 2007, 97.1% of audiology patients in Herefordshire PCT waited longer than 13 weeks, compared with none in Worcestershire PCT , despite the fact that Worcestershire PCT diagnosed over four times as many (4,771 compared with 1,153).

These differences cannot be explained away by differences in demand, or workload; it is not the case that the South East Coast SHA are struggling to treat patients within 18 weeks because they simply have to treat more patients. Capacity – a separate variable – obviously comes into the equation, but the two best performing SHAs, West Midlands and North West, also treated the most patients overall in September 2007, whereas South East Coast SHA actually treated the least. There is, in fact, no correlation between number of patients treated and waiting times:

Percentage of patients treated within 18 weeks of referral in each SHA, vis-à-vis number of patients treated, England, September 2007

Source: Department of Health

Once again, we come back to the old bugbear of the NHS: the postcode lottery. Some hospitals and primary care trusts are simply very inefficient, which is bad news for the people living in their catchment areas.

However, there is now an escape route, cemented in the NHS Operating Framework for 2008/9: competition. As of April 2008 all patients will be able to choose between all DH-approved providersanywhere in the country for elective operations, including independent providers. As is the case elsewhere, the ability of patients to compliment, complain and ultimately take their ‘business’ elsewhere will drive providers in the NHS to improve. Patients who are prepared to travel to a better-performing hospital outside their own area will be able to receive more speedy treatment; if this means more patients choosing to have their treatment in the independent sector, then the sector should be allowed to expand in response to this. Indeed, the evidence suggests that where independent provision – in the form of independent sector treatment centres (ISTCs) – have been brought in they have made a significant impact on local performance and waiting lists:

‘The fact that Somerset PCT has one of the highest proportions of patients treated within the target (79%) is in part down to the fact it has been able to take advantage of a highly successful ISTC – the well-documented Shepton Mallet Treatment Centre – in its midst. Dubbed the ‘Shepton Mallet effect’, the ISTC has, very literally, shaken up NHS providers and bumped trusts such as Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, with 88% of patients treated within 18 weeks, and Taunton and Somerset NHS Trust with 76%, to the top of the RTT ‘leaderboard’.

By contrast, it’s not going to help West Hertfordshire PCT that it’s surrounded by hospital groups such as West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust and East & North Hertfordshire NHS Trust, where the percentage of patients treated within 18 weeks stood at 23% and 36% respectively in September 2007. Both were also rated ‘weak’ on use of resources, with West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust also scoring ‘weak’ for quality of care, by the Healthcare Commission in its annual health check for 2006/07. Perhaps not so coincidentally, it’s also in a region – East of England SHA – where there’s not an ISTC in sight.’

However, much depends on the attitudes of primary care trusts (PCTs) and GPs – the gatekeepers to this system. Patients depend on their GPs to make information about choice available to them, but the evidence so far is not encouraging:

- The utilisation of ISTCs is still below capacity, despite all the evidence pointing to better standards of care;

- The number of patients who recalled being offered a choice of hospital for their first outpatient appointment actually fell by 5% between March and July 2007 to a very lowly 43%;

- Just 45% of GP referrals are using the Choose and Book system, which is necessary to access the benefits of competition.

According to John Appleby, chief economist of the King’s Fund: ‘Commissioners appear to be analytically underpowered and nervous about destabilising existing provider networks, and they behave as if they want to revert to central control and provider protectionism’.

As James Gubb puts it:

‘It must now be down to PCTs and GPs to encourage choice and competition to ensure the window of opportunity that has been provided isn’t missed. For the benefits of competition to be realised, and for waiting times to really accelerate downwards, the reluctance of commissioners to use independent providers at the expense of established NHS providers has to change – and fast.’

*All analysis of RTT data refers to admitted patients only. Best and worst figures for NHS Trusts/Foundation Trusts only include those that carried out more than 100 elective operations( where the known clock stopped in September 2007) and in more than one specialty.

For more information ring:

James Gubb 07930 243570

Robert Whelan 07732 674476

The full report is available below.

Why are we waiting?