Boosting UK Exports: Improving export finance for small businesses

Christian Stensrud, March 2017

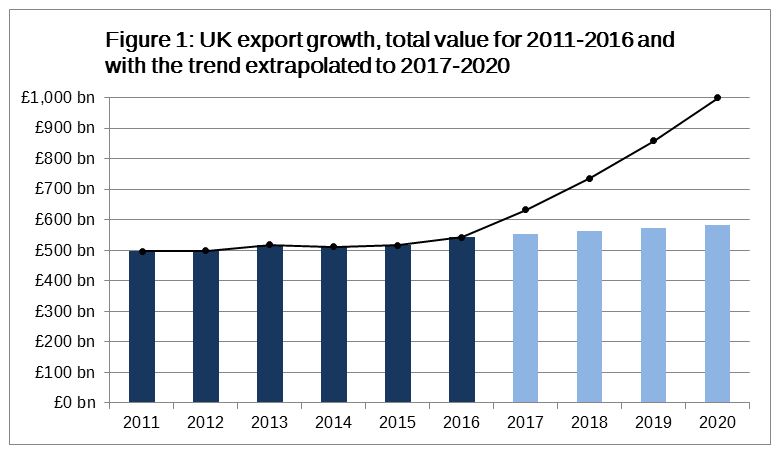

Theresa May has pledged to turn Britain into a ‘great, global trading nation’. To help fulfil this goal, the government is trying to improve the UK’s export performance. The desired improvement is shown by the government’s current export targets: increase the value of exports to £1 trillion by 2020, and increase the number of exporters from 188,000 in 2010 to 288,000 by 2020.

Theresa May has pledged to turn Britain into a ‘great, global trading nation’. To help fulfil this goal, the government is trying to improve the UK’s export performance. The desired improvement is shown by the government’s current export targets: increase the value of exports to £1 trillion by 2020, and increase the number of exporters from 188,000 in 2010 to 288,000 by 2020.

However, neither of these targets are being met. According to Civitas calculations, exports will have to grow by 16 per cent a year to hit the £1 trillion target (shown by the black line in Figure 1). This is much higher than the annual growth rate of two per cent between 2011 and 2016. The latest total export figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) are shown by the dark blue bars. On the current trajectory, total exports will miss the target by £417 billion (shown by the light blue bars).

The target to increase the number of exporters to 288,000 by 2020 is more achievable. The total number of exporters increased from 188,000 in 2010 to 228,700 in 2015. At the current growth rate, there would be 278,211 exporters in 2020. However, this still misses the target by almost 10,000.

What’s troubling is it’s not clear where the required boost in exports will come from. Whilst sterling’s depreciation should improve export performance, it will not be enough to deliver £1 trillion of exports in 2020. Moreover, the lacklustre export performance means that the UK’s current export strategy will most likely fail to deliver the boost required. Indeed, a recent select committee inquiry into the UK’s strategy cites numerous areas of concern, including a lack of export finance compared to other countries; a lack of support for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs); and a lack of coordination amongst local government, national government and business groups.

If the government wants to take advantage of sterling’s depreciation and change the UK into ‘one of the great trading nations in the world’, then it must offer new and effective export promotion policies that help businesses to either start exporting or to increase their global reach.

- Where to target export policy?

According to economic research, increasing the number of exporters is more important for a country’s trade performance than increasing the involvement of firms already exporting. The UK government should, therefore, focus on increasing the aggregate number of exporters. There is plenty of potential in pursuing such a policy; it is estimated that between 25,000 and 150,000 currently non-exporting firms could export on a sustainable and continuous basis.

Moreover, new exporters usually account for an extremely large proportion of export growth over a medium to long-period (5 to 10 years). Between 2005 and 2011, 52 per cent of the UK’s export growth in goods to non-EU countries was created by new exporters (those who weren’t exporters at the beginning of the period but became exporters by the end of it). The same trend is seen in services. However, the evidence is not as conclusive.

Both SMEs and larger firms (250+ employees) accounted for a large share of new entrants’ contribution to export growth. Any new export strategy should, therefore, unearth more exporters from both groups. In particular, the growth in SME exporters has been lacklustre, with the percentage of SMEs that export remaining at 11 per cent between 2011 and 2015.As such, this report will focus on encouraging more SME exporters.

- Access to finance

According to a recent select committee inquiry, accessing the finance required to alleviate the costs and risks of exporting seems to be a barrier faced by many SMEs. According to other evidence, 60 per cent of potential exporters cite access to finance as a key factor in their export plans, and 24 per cent of UK businesses preparing to export have reported difficulties in accessing trade finance or credit insurance from lenders.

One of the most important organisations for export finance, perhaps the most important, is the UK’s export credit agency (ECA): UK Export Finance (UKEF). The agency’s role is to ensure that no viable UK export fails for lack of finance or insurance. It tries to achieve this principally by providing insurance to UK exporters against non-payment, guarantees to banks to support working capital financing and raising of contract bonds, guarantees to banks and investors in the debt capital markets in respect of loans to overseas buyers of UK exports, and lending directly to overseas buyers who purchase from UK exporters.

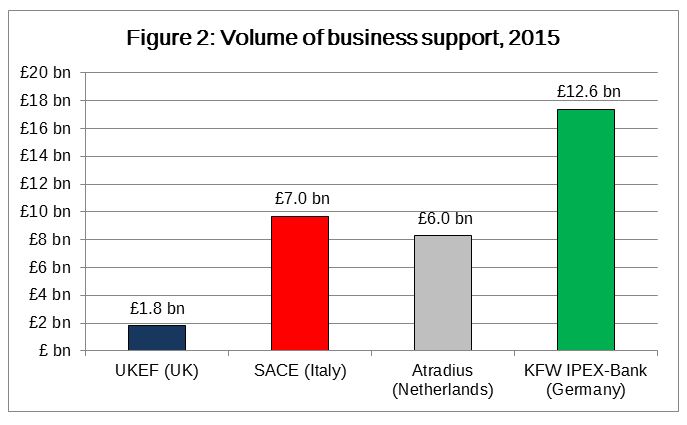

UKEF has improved over the past five years, offering a wider variety of financial products, more innovative solutions to financing issues and helping more small exporters. However, the agency still lags behind many other European ECAs when it comes to supporting exporters. For example, in 2015 UKEF supported 279 companies, and the maximum liability on all new business was £1.8 billion. In comparison, Italy’s ECA, SACE, approved €9.7 billion (£7 billion) of new guarantees in 2015 and Atradius, the Netherlands’ ECA, provided €8.3 billion (£6 billion). UK exporters are even more disadvantaged when it comes to the largest export credit agencies. In 2015 China, via one of its ECAs Sinosure, committed approximately $364 billion (£248 billion) to new short-term export credits and working capital volumes. This is nearly 140 times the value of UK support in an economy only four times larger.

This gulf in support should be partly bridged by the increase in UKEF’s capacity announced in the Autumn Statement. One of the most poignant interventions was to increase the capacity for support in individual markets by up to 100 per cent. Market cover limits were previously capped at £2.5 billion, but UKEF can now double that limit to £5 billion. This gives UKEF more ability to meet its £50 billion portfolio capacity (UKEF’s current exposure is approximately £20 billion).

However, the chronic lack of support compared with peers shows that UKEF may be too risk averse compared with many other ECAs. For UKEF to be competitive, it must maintain a balance between fiscal responsibility and a willingness to absorb a level of risk necessary to be competitive with its ECA counterparts. The increase in market cover limits is a good step towards balancing the scales, but more needs to be done. The next steps are to diversify the products and services offered to SMEs and to raise awareness amongst SMEs about UKEF.

Foreign exchange rate risk cover

Foreign buyers are increasingly preferring to trade in their local currencies to avoid exposure to fluctuations in exchange rates. This puts UK SMEs that export in a tricky position. They can either accept these terms and become exposed to potential financial losses due to a subsequent devaluation of that foreign currency against sterling. Or they can insist on selling in sterling, resulting in lost export opportunities to foreign competitors who are willing to accommodate the foreign buyer.

For many SMEs that sell in foreign currencies, foreign exchange risk is a big problem, and many see either gains or losses because of exchange rate fluctuations. According to a recent survey of small UK exporters, foreign exchange rates are the most cited challenge to exporting.

Specific strategies can help firms manage or hedge foreign exchange risk, including hedging tools such as forward contracts or options. However, according to many SMEs, it is too complicated and expensive to create and maintain an effective hedging strategy. Many SMEs do not have a specialised resource within their finance department to deal with foreign exchange risk management, and many lack the knowledge, experience and product understanding required. Thus, approximately 65 per cent of UK SMEs do not use hedging tools to mitigate foreign exchange risk.

In fact, to mitigate foreign exchange risk many SME exporters ask for cash upfront. This is an uncompetitive strategy; many foreign buyers want to pay later due to cash flow considerations, and many foreign exporters are willing to acquiesce. Helping SMEs sell in foreign currencies to a buyer that will pay at a later date will help increase their competitiveness, but only if foreign exchange risk is successfully managed or hedged.

UKEF should offer foreign exchange risk cover. Other countries’ ECAs already offer this, including those in France, the Netherlands and South Korea. By offering foreign exchange risk cover via one government agency and one product, the process of mitigating foreign exchange risk becomes much simpler for SMEs.

The Netherlands’ ECA, Atradius, offers a framework for such a policy. Their Currency Risk Insurance offers a guaranteed exchange rate that is valid on the expiry date of an insured tender period (capped at 36 months). For this cover the exporter must pay a premium, consisting of a fixed and variable component. The fixed component amounts to 0.5 per cent of the contract sum insured, and the variable component amounts to a monthly sum: 0.1667 per cent for a standard currency and 0.25 per cent for a specialist currency.

The scheme, from Atradius’s perspective, seems affordable. In 2015 claims paid under foreign exchange rate risk insurance policies totalled €700,000. This compares favourably to the €96.4 million paid out under its Export Credit Insurance facility, and it shows that foreign exchange cover can be provided prudentially.

This is one measure that UKEF could clearly use to alleviate one of the biggest barriers to SME exports whilst also maintaining the right balance between risk and fiscal responsibility.

A department for SMEs

According to the Cole Commission, businesses commonly asserted that UKEF applies a burdensome assessment process that is not beneficial to SMEs. In addition, businesses stated that support is often denied on the basis of the SME having no export experience or because the value of the deal is too low. It’s clear that UKEF, whilst making progress in SME assistance over the years, still needs to be more receptive to the needs of SMEs.

Because SMEs’ needs differ to those of bigger firms when it comes to export finance, UKEF should establish a department dedicated solely to working with SMEs. A good example is provided by Denmark’s ECA, EKF, which established a department for SMEs in 2010. Compared to EKF’s department for large businesses, the SME department offers swift and flexible processing times. In addition, the employees have a more generalist skill set compared to their counterparts in departments that deal with large exporters, primarily because they must familiarise themselves with a large number of small businesses.

The creation of this SME department has led to new products being developed by EKF that specifically target SMEs. This shows that a SME department could make UKEF more receptive to SMEs’ needs and concerns, creating a dynamic that leads to more effective SME export financing products.

In fact, UKEF could take inspiration from one of the products: the Capital Expenditure Guarantee. EKF issues a guarantee to the exporter’s bank for a capital expenditure loan, providing the security the bank needs to grant the loan. The loan is then used by the exporter to invest in the production facilities and machinery needed to export. By helping Danish companies establish production facilities and machinery, the guarantee helps firms invest in growth, keep up with new demand and confidently reach out to new markets.

This is attractive for the UK for a number of reasons. Firstly, many UK firms suffer from a lack of investment. In addition, it makes it easier for UK firms to invest in production facilities in the UK, both creating jobs and ensuring firms can satisfy demand from new export ventures.

As a result of EKF’s focus via its SME department and SME products, the ECA assisted 556 SMEs with export credits or working capital guarantees in 2015. This is much higher than the 137 SMEs helped by UKEF.

Raising awareness

A large number of SMEs are not aware of UKEF nor of the assistance it can offer. This is partly because SMEs do not have the finance expertise to keep abreast of the latest financial products, offered by ECAs, insurers or banks, that can help them mitigate the risks and costs of exporting. This knowledge gap means that many SMEs who could export are not doing so.

The government needs to stimulate an outreach programme that could target SMEs capable of entering the export market with support from UKEF. Whilst the structure of this programme is open to debate, other European ECAs offer examples of outreach programmes.

Netherlands’ export credit agency, Atradius, launched a programme in 2015 that aimed to make its services more widely known to SMEs that sold capital goods or services abroad. The agency gathered information from various sources and subsequently built a database containing information about these SMEs, many of which were not clients of Atradius. At the end of 2015, the agency conducted an email campaign to increase awareness of its brand and product range.

Another strategy is offered by Denmark’s ECA, EKF. Recently, EKF conducted a massive marketing campaign which focused on SMEs. This included full page adverts in national newspapers, TV adverts, and banner advertising. In addition, EKF organises workshops that attempts to bring together participants in the export financing process, including exporters, insurers and financiers.

As a result of the campaign, the percentage of SMEs that were aware of EKF rose from 40 per cent in 2012 to 90 per cent in 2015. Higher awareness resulted in larger levels of new guarantees issued to SMEs, issuing nearly €250 million (£202 million) worth in 2014. This was the highest exposure to date and a 13 per cent increase on the year before.

UKEF should use the above examples to create an outreach campaign that can increase SMEs’ awareness of UKEF. If successful, EKF has shown that increased awareness can lead to increased levels of support for SMEs.

Conclusion

SMEs with the potential to export should be a focus of any government strategy that seeks to boost the value of UK exports. This paper has highlighted a number of ways in which the government could help SMEs realise their full potential as exporters via UKEF, including new products like foreign exchange risk cover and a capital expenditure guarantee, a new department for SMEs within UKEF, and an awareness campaign. These policies would help the government achieve its goal of turning the UK into a ‘great, global trading nation’.

About the Author

Christian Stensrud is a Research Fellow at Civitas. He can be emailed at christian.stensrud@civitas.org.uk and tweets @Christian_Stens.

Download PDF