One million homes by 2020? It could be done – but it would be a long way short of what is needed

Daniel Bentley, 15 November 2016

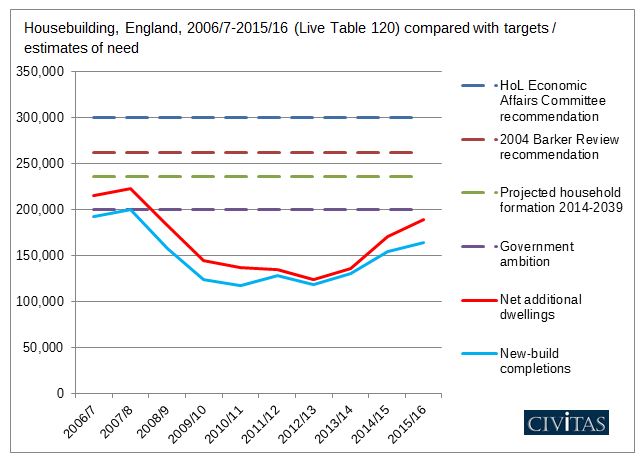

The results are in on housebuilding efforts during the first of the five years of the current parliament. The government’s ambition – reaffirmed under Theresa May’s new leadership – is to build a million homes by 2020, which would be an average of 200,000 a year. The net supply of housing statistics for 2015/16, published this morning, offer the first comprehensive picture of progress against this target. A few quick takes:

- The government is already behind on its one million homes ambition, although it is not unrealistic to imagine that it could still be achieved. Housing supply was up 11 per cent on the previous year, but to just 189,650, so the numbers are already about 10,000 units down on where they would need to be unless the difference can be made up later. As David O’Leary of the Home Builders Federation points out, however, this would only require a 1.15 per cent year-on-year increase for the rest of the parliament, which does not sound unrealistic.

- A significant portion of this increase in net supply came from converting non-domestic premises into homes, as opposed to new-build properties. The number of new homes coming from ‘change of use’ (from offices, storage buildings, agricultural buildings etc) has risen dramatically in the past few years, from 12,520 in 2013/14 to 30,600 in 2015/16. This is thanks in large part to the introduction of ‘permitted development rights’ where full planning permission is not required. Homes are homes, so there is nothing wrong with counting these units towards the supply of new housing, but in the headline figures they do disguise something else…

- The annual increase in new-build completions was the lowest it has been during the post-2008 recovery. Because of the disproportionate rise in ‘change of use’, the 11 per cent rise in net supply is not representative of the rise in the actual building of new homes. New-build completions were up only 5.7 per cent, by 8,860 units to a total of 163,940. This represents a slowdown after two years of much quicker growth (by c.12,000 units in 2012/14 and by c.15,000 units in 2014/15).

- London, where the supply/demand imbalance is most acute, increased output but is still a long, long way behind building enough homes. The national figures disguise the all-important regional distribution, and analysing that in any depth will take a bit of time. But there is little doubt that the shortfall of homes in the capital is only worsening despite a creditable increase in output from 26,840 in 2014/15 to 30,390 last year. This is still little more than half London’s housebuilding target of 49,000 homes a year.

The bottom line is, however, that the government is not far off hitting its one million homes ambition. But it is important to remember that this is an arbitrary political target which bears no resemblance to the actual level of housing need in England.

The Department for Communities and Local Government projects the formation of 236,000 households a year between 2014 and 2019. Some dispute these projections given that they don’t often square with reality (see this thread from Neal Hudson at Savills) but they remain Whitehall’s best estimates of future pressures. In any case, that figure is still lower than the number of homes that most independent bodies suggest is needed to keep house price inflation to a minimum. The landmark Barker Review recommended back in 2004 that there would need to be 245,000 private-sector homes a year, plus another 17,000 social housing units (totalling 262,000), to keep house price inflation down to 1.1 per cent per annum.

Kate Barker, who chaired that review, has recently suggested that this figure might now need revising up to 300,000 homes a year: ‘I would say that if the objective over the next five years is to keep the affordability of housing no worse than it is today, or even to lower it a little bit, we would probably need to be building around 300,000 houses a year or in excess of that. We would also have to build them in places where there is demand. Obviously, if we built them all around Sheffield it would not be very useful. If we spread them around the country, particularly in places of high demand, it would be more useful. It would be numbers of that order.’

The cross-party House of Lords Economic Affairs Committee, whose members include the former chancellors Alistair Darling and Norman Lamont, and the former cabinet secretary Andrew Turnbull, endorsed this 300,000 figure in July 2016: ‘It has been ten years since 200,000 homes (the implied annual rate from the Government’s target) were added to the housing stock in a single year. But the evidence we have heard suggests this will not be enough to meet future demand and the backlog from previous years of undersupply. To meet that demand and have a moderating effect on house prices, at least 300,000 homes a year need to be built for the foreseeable future. Otherwise the average age of a first time buyer will continue to rise.’ The Town and Country Planning Association has suggested that, to make up for the shortfall in housing supply that has taken place just since 2011, 312,000 homes a year would be needed for the next five years.

The government needs to be much more ambitious about its housebuilding targets, therefore. Even if it hits its one million homes target, the backlog between housebuilding and projected households would continue to grow by 36,000 homes a year – 180,000 homes across the parliament. If the government wants to prevent housing becoming ever more expensive, it will need a strategy for delivering in the region of 300,000 homes a year rather than 200,000; against that objective England would be another half a million homes short by 2020 if it does not raise its ambition.

As ministers prepare a new housing white paper, they ought to first take stock of the scale of the housebuilding challenge and revise up their ambitions correspondingly. One million homes by 2020 must not be regarded as ‘success’ but as yet more failure. A strategy for success will not be built on an under-estimate of the scale of the problem.

Daniel Bentley is editorial director at Civitas and author of ‘The Housing Question: Overcoming the shortage of homes’. He tweets @danielbentley

What about this idea?

http://www.adam-knight.org/blog/housing